What is Abstract Expressionism? How did it skyrocket in popularity across the globe, and why does it hold a dominant position in the history of modern art to this day? Who started it? Who celebrated it? And what was so radical about Jackson Polloсk's art that earned him a nickname "Jack the Dripper"? Let's find out in this episode from Curious Muse!

For centuries, Paris was the global center of artistic innovation. But that all changed when a group of artists coming from the New York City area after the Second World War brought exciting new advances to painting. Together, they were called Abstract Expressionists because all of their paintings were predominantly abstract and each embodied the emotional expression of the artists. You may be familiar with another term - the New York School - which many art historians consider a more appropriate name for this distinctive aesthetic that emerged in the late 1940s and early 1950s and placed the Big Apple at the center of the world's art stage.

The New York School brought together artists who were inspired by war and the human irrationality and vulnerability it exposed. Many of them shared strong beliefs based on Marxist social and economic equality ideas, including Robert Motherwell, Clyfford Still, Jackson Pollock, and Ad Reinhardt. They gravitated towards the Existentialist philosophy of Jean-Paul Sartre and Carl Jung’s collective unconscious aiming to communicate universal truths about the human condition. AbEx artists were not interested in the subject or meaning of their paintings and even stopped naming their works.

Instead, Abstract Expressionists emphasized discovery and an aesthetic experience, hoping to evoke strong emotions as well as different interpretations. To them, abstract art was the perfect visual language to achieve all of this. This unique form of art was first exhibited in New York as early as the 1930s, together with other movements of European Modernism, such as Cubism, German Expressionism, Dada, and Surrealism. All these ideas and practices, including Native American Art and even Asian calligraphy, profoundly impacted AbEx artists.

Abstract Expressionism was the first American art movement to achieve international acclaim. This was largely thanks to the U.S. government, which saw the new style as a reflection of American democracy and freedom and spent millions of dollars actively promoting the movement around the world as part of its political propaganda. Clement Greenberg and Harold Rosenberg, two influential art critics, also helped wrap peoples' brains around these often baffling paintings. Finally, Abstract Expressionists were very fortunate to have Peggy Guggenheim, a wealthy American art collector, on their side. With her support, The New York School became a tremendous financial success.

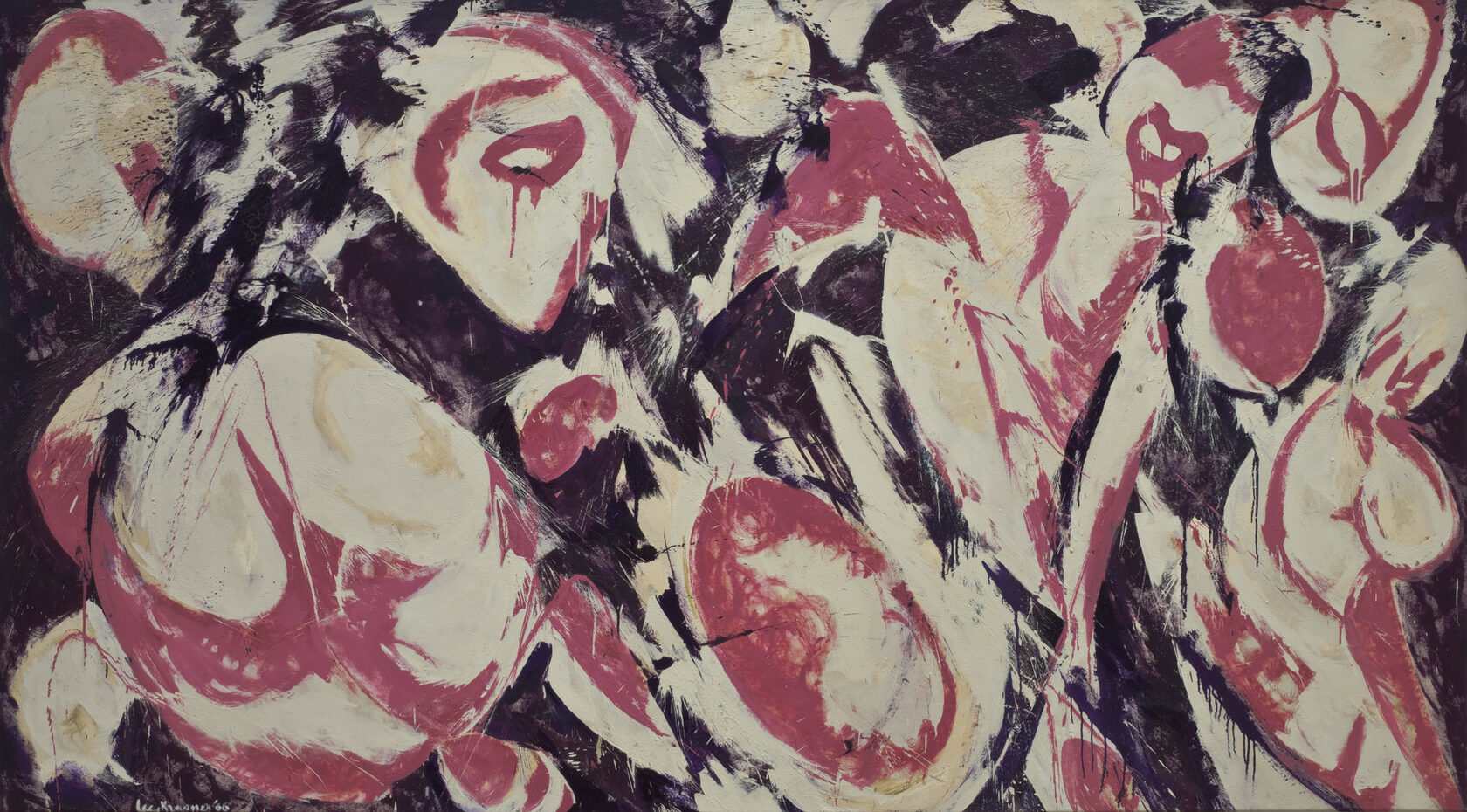

Importantly, the artists also supported each other. Most AbEx artists were friends, some of them even lovers, who lived and worked together organizing exhibitions and discussing art at the legendary Cedar Tavern. The community sometimes created rivalries or overshadowed other incredible artists. For example, Lee Krasner and Elaine de Kooning's work has only recently started to be appreciated by critics without comparisons to the art of their famous husbands. Yeah, the art world in post-war America was pretty much a man’s world, a macho environment personified in the famous bohemian and rebel Jackson Pollock.

Although sometimes perceived as a unified movement, Abstract Expressionism was a much more complex phenomenon in art history in terms of styles and approaches. Yes, most abstract expressionist paintings are large in scale, denying a formal concept of the composition and including non-objective imagery. Still, the way the painters dealt with abstraction is quite different depending on the artist.

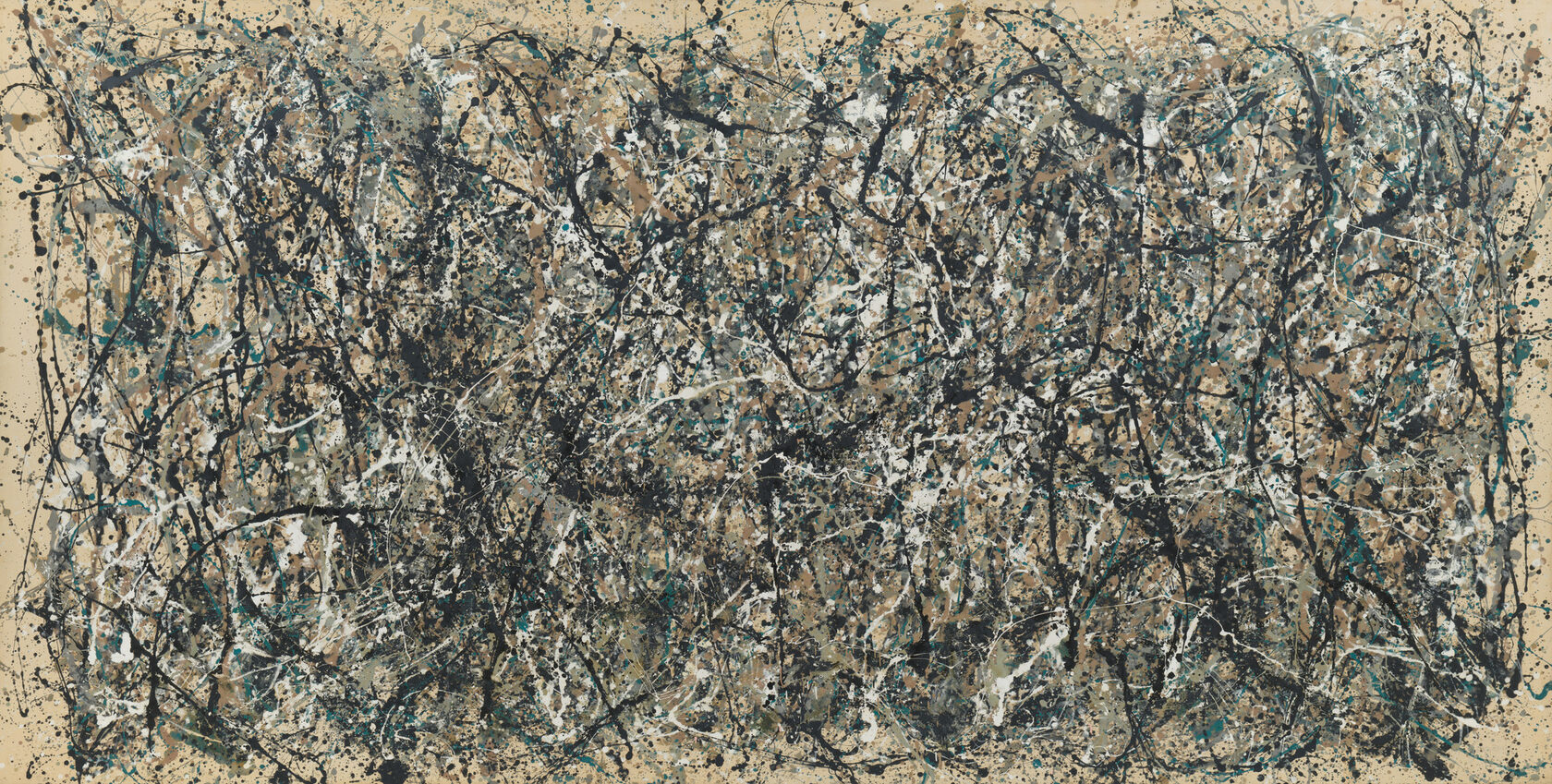

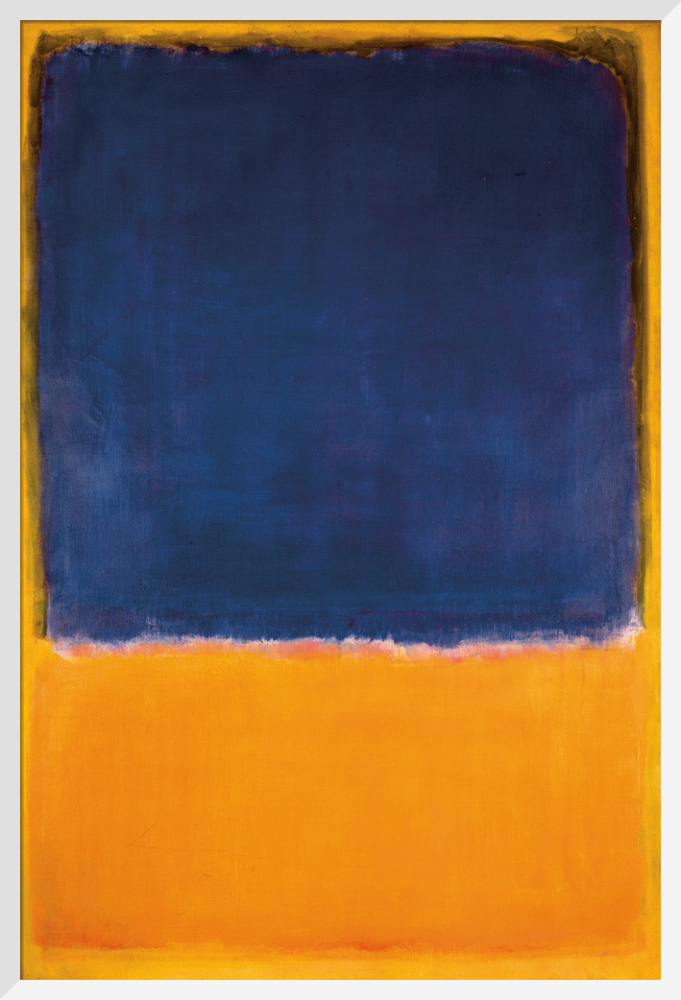

Each of the artists involved with The New York School developed an individual style that can be easily recognized. Barnett Newman did his iconic existential zips, Jackson Pollock poured paint, Helen Frankenthaler soak-stained her paintings, and Rothko allegedly achieved the sublime in art through his fluid forms and radiant hues. Nevertheless, there are two broad groupings within abstract expressionism: action painting, and color field painting.

For action painters, the actual act of painting was paramount. The style was characterized by extremely vigorous and expressive handling of paint, sweeping brush strokes, and, in the case of Jackson Pollock, pouring and dripping commercial paints with sticks and knives directly onto an untouched canvas spread out on the floor. This radical technique, which earned him the nickname “Jack the Dripper,” allowed Pollock to break away from traditional painting processes and express his inner psyche freely and spontaneously. Inspired by the automatism of Surrealists and sand painting of Navajo artists, Pollock regarded the canvas as a painting arena on which he recorded the "action" of painting without any restrictions. The final product is a pulsating web of tangled lines in which there is no where our eyes can rest. Although Pollock’s works may seem as if they have been made in a frenzy, they all have structure. They look wild but at the same time possess great subtlety.

The less emotionally expressive and more cerebral and philosophical approach was the color field painting, practiced by artists such as Clyfford Still, Barnett Newman, Adolph Gottlieb, Hans Hofmann, Helen Frankenthaler, Kenneth Noland, Ad Reinhardt, and Mark Rothko. These artists created simple compositions with large areas of flat color to provoke a contemplative response in the viewer. The master of color, Rothko, applied thin layers of paint, one on top of the other, to create glowing hues that almost illuminated the painting from within. This achieved a sense of atmospheric depth. Rothko wanted his paintings to do what Mozart had done in music: inspire a spiritual experience in art viewing and bring tears to the eyes of his viewers.

However, by the 1960s, these philosophical overtones of Abstract Expressionism became increasingly at odds with a society preoccupied with consumerism and the mass media, leading to the end of the movement and the emergence of Pop Art.